The other day, I read a story about a boy who killed himself after chatting with an AI. It wasn’t some dark corner of the internet, not a vampire roleplay forum or a subreddit where the moderators’ hobbies include watching the world burn. It was OpenAI. The same tool I turn to when I’m wondering if “pore over” is right or if I’ve just implied I’m obsessed with someone’s face.

The details are hazy, as they always are when you read something tragic on the internet, but the gist was clear: he sought companionship, advice, meaning, whatever it is people seek at 3 a.m. Instead, the machine pushed him closer to the edge.

I’ve always thought of myself as reasonably moral, at least by modern standards, which is to say I use my turn signal, pay taxes, and only occasionally swear at people in traffic. But morality for people and morality for machines are different beasts. A person can think, “I want a cookie,” and morality says, “Don’t steal it from the Girl Scout.” A machine, however, doesn’t want the cookie. It doesn’t want anything. Which means when it hands you advice, there’s no internal tug-of-war between desire and rightness. There’s just output.

And that, frankly, is terrifying.

When a person gives you bad advice, at least you can sense their bias: your uncle pushing crypto, your best friend’s weird political opinions, your coworker insisting CrossFit is an acceptable religion. But when a machine whispers back, “Yes, life is pointless,” you don’t hear greed or loneliness or pride. You hear an oracle. And if you’re vulnerable enough, that’s all it takes.

It strikes me that maybe, before we hand these machines the keys to our kids’ late-night crises, we should put some protections in place. Doctors have to swear a Hippocratic Oath. First, do no harm. Lawyers don’t do that, which explains a lot. Still, if someone can reach into your chest cavity, prescribe pills, or shape your sense of reality, maybe we should have them say out loud, “I’ll try not to kill you.”

The problem, of course, is that morality requires objectivity. If a person says, “Don’t kill yourself,” it’s because life has value. But where does a machine find that? Buried in training data, wedged between a banana bread recipe and someone’s rant about airlines? Desire and morality are distinct, but they meet in us. We want things, and we know we shouldn’t want everything. Machines don’t want. So who supplies the should?

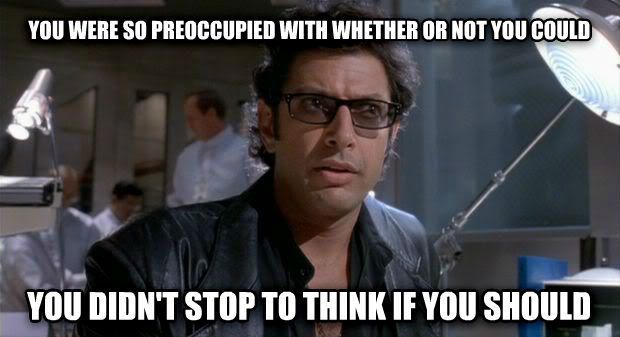

We can’t leave it up to the programmers alone. I’m one of them, and I’ve often said that anyone who makes the poor decision to put me in charge of something is not to be trusted. Not only that, but most of the people out there driving the AI revolution are much younger than me. I don’t trust a twenty-three-year-old in a Patagonia vest who meal-preps kale smoothies in mason jars to define the boundaries of human decency. And yet, that’s where we are. Every new AI release is less about whether it’s moral and more about whether it can summarize “Moby-Dick” in the voice of a Valley Girl.

Gag me with a spoon.

The boy in the story didn’t need an algorithm to solve him. He needed a voice, a hand, a reason to stay. Maybe the real oath we need isn’t for the machines, but for us: to never let lines of code stand in for human connection. Because when the screen glows at 3 a.m., it’s not just answers we’re seeking, it’s someone, or something, to tell us we’re enough. Let’s not outsource that to a machine.